“Secular Relics: Casement’s Boat, Casement’s Dish,” in Textual Practice (Summer 2002), pages 277 – 302

by permission of Professor Lucy McDiarmid (author of At Home in the Revolution: what women said and did in 1916, published by the Royal Irish Academy, November 2015) www.lucymcdiarmid.com

Secular relics: Casement’s boat, Casement’s dish

‘An té a bhíonn go maith duit, bí go maith dhó,’

mar a dúirt Cailleach Bhéarra le Cailleach Mhaigh Eo.’ ‘The one who’s good to you, be good to him,’ as the Witch of Beare said to the Witch of Mayo.’ (proverb)

The moment Roger Casement landed on Irish soil in North Kerry on 21 April, Good Friday, 1916, around two-thirty in the morning, grand, magical transformations took place. The small wooden rowboat carrying Casement and two companions from the German U-boat had overturned in the waves, and the men pulled it along as they swam ashore. Soaking wet, exhausted, Casement touched Banna Strand and fell asleep. A change occurred: his body became a collection of future First-class relics, his clothing and possessions future second-class relics, and all the paraphernalia he brought ashore instant memorabilia. At that moment Banna Strand itself became a charismatic landscape, a place of supernatural power, a point of pilgrimage.1

Even before the people of North Kerry were aware that a patriot ready to die for Ireland had landed in their midst, objects • ew from the scene. By four in the morning, when Casement and the others had gone inland, the boat had been claimed as salvage by the First local resident who saw it, John McCarthy, though it was appropriated by the police before it could be sold.2 By nine in the morning, the dagger (one of several weapons in the pile of equipment not quite hidden in the sand) had been taken by Thomas Lyons, whose nephew mentioned the theft in a letter thirty-six years later.3 Another of those weapons, a 1914 Mauser pistol, now forms one of the exhibits in the Royal Ulster Constabulary Museum in Belfast.4 Imprisoned overnight in the police barracks in Tralee, Casement himself (following the practice of the United Irish martyrs) distributed his possessions, their authenticity validated by the touch of the future martyr: his pocket watch went to Chief Constable Kearney, his walking stick to Sergeant Hearn, and his waist-coat to another constable.5 Long after that fateful Good Friday, objects linked to the landing continued to disappear. The ordnance survey map of Ballyheigue Bay, gathered by the Royal Irish Constabulary as evidence against Casement at his trial for treason, was surreptitiously carried from court afterwards by solicitor Charles Gavan Duffy, who returned it in the 1950s to Robert Monteith, one of the men who landed with Casement. Monteith gave it to Brother William P. Allen, and it remains to this day in the Allen Library of the Christian Brothers School on North Richmond Street in Dublin.6 When the wooden ‘Casement boat’ was sent to the naval yard in Haulbowline later in 1916, Ned Donovan, who worked there, took a little handsaw he found under the seat ‘as a souvenir’. When the boat emerged into public view again in 1950, he still had the saw.7

Extraordinary powers were attributed to the spot where Casement First touched land. They must have been activated at that moment, because Casement felt the landscape’s magic. ‘When I landed in Ireland that morning,’ he wrote to his sister Nina Newman from prison, swamped and swimming ashore on an unknown strand I was happy for the First time for over a year. Although I knew that this fate waited on me, I was for one brief spell happy and smiling once more. I cannot tell you what I felt. The sandhills were full of skylarks, rising in the dawn, the first I had heard for years – the first sound I heard through the surf was their song as I waded in through the breakers, and they kept rising all the time up to the old rath at Currahane [sic] . . . and all round were primroses and wild violets and the singing of the skylarks in the air, and I was back in Ireland again.8

The charismatic power of the place, so easily channelled into the local economy, was noted a few months later by John Collins of Ardfert, whose licensing application for a hotel on the spot was noted in the Kerry Sentinel:

Counsel pointed out the necessity for a suitable hotel in this place.

. . If a place like this were in England it would be overrun, but being in Ireland it is not. An unfortunate incident that occurred there lately may have that effect, that was the landing of Sir Roger Casement at the place. That was a matter which will go down in history, a matter of great historical interest, and when all the feelings of bitterness will be past and gone McKenna’s fort and Banna Strand will be of great historical interest, and people will be anxious to go there.9

The spot is now marked by the monumental Casement memorial, identified on the current ordnance survey map in the area just north of Carrahane. McKenna’s Fort, where Casement hid and was captured, is now Casement’s Fort. Inland from the memorial stands ‘Sir Roger’s Caravan & Camping Park’, its presence testifying to the way pilgrimage and tourism, sacred and secular, transmute into one another like the planes on a mobius strip.

The transformation that took place with Casement’s landing also involved the people of North Kerry: everyone he met became politically implicated as a traitor to the Crown or a traitor to Ireland, spiritually impli-cated as someone who had helped or hindered a martyr, legally a witness, and a participant one way or another in a narrative whose smallest details were passed on to later generations, personal memories that constituted local collective memory. The name too became magic in Kerry: when, sometime in the 1970s, Casement’s collateral descendant Patrick Casement and his wife Anne were driving through Kerry and had work done on their car at a garage in Killarney, the mechanic, seeing the name on the cheque, refused to accept payment.10

What is ‘significant about the adoption of alien objects,’ writes Igor Kopytoff, ‘is not the fact that they are adopted, but the way they are culturally redefined and put to use.’ A ‘culturally informed’ biography of an object would regard it ‘as a culturally constructed entity, endowed with culturally specific meanings and classified and reclassified into culturally constituted categories’.11 Such a methodology would shed light on the biographies of two non-indigenous objects now in North Kerry, a German rowboat – the ‘alleged Casement boat’ – in the North Kerry Museum of the Rattoo Heritage Centre, and an English meat platter in the staffroom of Scoil Mhic Easmainn (Casement School) in Tralee. This is the platter from which Casement is said to have eaten his meals during the appeal of his death sentence in July 1916. To understand the larger system that has endowed these objects with meaning, the system that has reimagined and redesignated them as relics, they must be placed in the context of collective memory of Casement in North Kerry.

National Irish collective memory of Casement is itself complex and disturbed, inseparable from the continuing debate about the authenticity of the ‘Black Diaries’, whose records of homosexual encounters may – or may not – have been authored by Casement. The apparent betrayal of a hero by his own people in Kerry also forms a part of national memory. In the words of Richard Murphy, watching Casement’s 1965 reinterment on television, it was the Kerry witnesses ‘whose welcome gaoled him’.12 In local memory, the narrative of Casement’s landing has been revised from that unhappy story to foreground the reciprocity – spiritual, emotional, political – between Casement and the people of Kerry. Caroline Bynum’s analysis of body-part relics argues that elaborate reliquaries ‘hide the process of putrefaction, equate bones with body and part with whole, and treat the body as the permanent locus of the person’.13 Objects that are second-class or ‘contact relics’ participate just as intensely in that synecdochic process. The Casement boat and Casement dish have been endowed with meanings that connect them intimately to narratives of reciprocity. Enshrined in North Kerry institutions, they receive the reverence and love that should have been given to the man himself.

The Kerry witnesses

‘Marbh ag tae, is marbh gan é.’

‘Dead from too much tea, and dead from the want of it.’

Because of Kerry’s failure to save Casement from execution and the failure of the Kerry Volunteers to participate in the Rising, stories and legends cluster around the approximately thirty-one hours Casement spent in Kerry. The local response has been to create monuments, speeches, ceremonies, Casement sites of memory that are corrective, remedial, compensatory, and ultimately sacralizing. The stories show the Kerry landing that should have been, the hero who comes out of the water to save the people, and the people who give the stranger a grand welcome. They establish Casement as a tutelary deity of the Ardfert region, almost replacing St Brendan, and Banna Strand as a landscape that is magical and sacred. Casement as a tutelary deity is in symbiotic relationship with the local people. In collec-tive memory of this episode he is the heroic liberator, but the people help a poor, tired, waterlogged stranger, warming and feeding and housing him. This is the rescue that never was, played out as in folktales when the stranger who comes to the door is recognized as God or a saint in disguise as a beggar.

During those thirty-one hours, Casement was the most seen unseen man in North Kerry. Just after midnight James Moriarty of Ballyheigue was up checking his rabbit traps and saw the • ashing lights of the U-boat out in the bay, but of course he did not know what or why it was signalling.14 Around four in the morning, Mary Gorman, the servant of John Allman in Rahoneen, saw three men (one of them very tall) passing by on the road. About two hours later, John McCarthy, on his way back from praying at a holy well, found the boat with a dagger in it. Michael Hussey, just back from gathering seaweed, thought he saw shapes and movement in the liss known as McKenna’s Fort, just up the dunes from Banna Strand. Later in the morning, McCarthy’s 7-year-old daughter found guns buried in the sand near the boat, and soon a small crowd had gathered around the boat and the arms.15

Around eight in the morning, the two men who had landed with Casement, Robert Monteith and Daniel Bailey, were put in touch with Austin Stack, Commandant of the Tralee Volunteers, and asked him to rescue Casement. Bailey and Stack set out along with Con Collins, another Volunteer, but they were stopped by the police, who arrested Stack and Collins.16 At one in the afternoon, when Constable Bernard Reilly, having heard all sorts of rumours, arrived at the fort (while Sergeant Thomas Ahern waited by the road), Casement did not give his real name or state his real purpose: he gave his English friend Richard Morten’s name and claimed to be the author of a biography of St Brendan. Around 1.15 p.m., 12-year-old Martin Collins came by with a pony and trap, doing the messages for the Allmans (Mrs Allman was his aunt, and it was her pony and trap), and noticed that as Casement, now arrested, was leaving the fort with Reilly, he dropped a piece of paper. Martin returned it to him later, but it was intercepted by the police. After stopping at the Allmans’ house, around 2.30 p.m. Reilly and Ahern took Casement to the barracks in Ardfert, where he was charged in the name of the Defence of the Realm Act with bringing arms into Ireland.17 Lizzie Boyle and her friends, out walking in Ardfert, noticed the commotion as a tall man was marched into the barracks.18

At the barracks in Tralee, where Casement was taken later and spent the night, District Inspector Britton said to him, ‘I think I know who you are, and I pray it won’t go the way of Wolfe Tone.’ Britton asked Casement why he had not shot the arresting constable and said he hoped Casement’s presence would not become known in Tralee, because then ‘the Volunteers would storm the barracks and “not a one of us would be left alive”’. Dr Michael Shanahan, who gave Casement aspirin, was shown Casement’s photograph by Head Constable Kearney and asked if that was the man he had just examined: ‘he said he thought not’, but then went to the Volunteers to get them to spring Casement. (Collins and Stack were locked up in neighbouring cells, but they never saw Casement.)19 Not wanting to give away the secret of the Rising, the remaining Volunteers purported not to believe it was really Casement. The next morning, the young Maurice Moynihan, later one of de Valera’s most trusted officials, saw Casement being marched from the barracks to the railway station (now Casement station).20 Casement’s presence in North Kerry had been an open secret, known and not known for thirty-one hours, but the power, the will and the opportunity to rescue him never quite coincided during that time, and on he was sent, under police escort, to Dublin and thence to London. Casement was hanged for High Treason on 3 August.

Casement’s stay in North Kerry was traumatic for everyone, those who failed to help him as well as those who betrayed him. A current resident of Tralee, who told me that Casement left an ‘imprint on our minds and hearts that was very disturbing’, did not want her name used or her sentence quoted in its entirety. Another resident of Tralee who also did not want his name used claims to have heard a balladeer sing a song about Casement so insulting to the people of Kerry that it could never be written down or even quoted. The ‘Kerry witnesses’, people like Mary Gorman who happened to look over the half-door of the Allmans’ house on to the road at four in the morning, were stigmatized in Kerry as traitors. The later police career of Head Constable John Kearney was ruined by his involvement with Casement, who had spent the night gaoled in the barracks.21 And in Tralee, they blamed it on Ardfert: in the 1940s and 1950s, when Ardfert footballers played against Tralee, they were taunted with the cry ‘Casement-killers!’22 The First poem ever published about Casement, ‘Banna Strand’, appears to blame the beach itself: ‘Oh, cruel star of destiny,/To guide him safe the wide world o’er,/To shield from perils far away,/And lose him on his native shore!’23

The return of Casement’s remains in 1965 brought the whole circumstances of his 1916 landing to national prominence, and the literature on the subject records the dominant attitude in the rest of Ireland. Richard Murphy’s poem ‘Casement’s Funeral’ is typical:

. . . our new Nation atones for her shawled motherland

Whose welcome gaoled him when a U-boat threw This rebel quixote soaked on Banna Strand.24

As Murphy interprets the Dublin ceremonies, they are atonement for the sins of the North Kerry witnesses, those backward people (‘her shawled motherland’) who did not give him the traditional Irish ‘welcome’ but ‘gaoled him’ when the poor man arrived helpless on their shores. David Rudkin’s radio play Cries from Casement as His Bones are Brought to Dublin represents the Kerry witnesses not only as guilty but as conscious of their own guilt and of their need to ask forgiveness. As ghosts, they visit his body while it lies in state in the church at Arbour Hill:

Young Kerryman. John MacCarthy, farmer, Curraghane, Kerry. On my road home through the dark that morning, after praying at a holy well – I said – saw your boat and the dagger in it; then sent for the RIC. I am sorry.

Young Kerry girl. Mary Gorman, farm girl, saw you that morning pass the gate. They said to me What time was that? Half-four, I said. Four thirty? they said. I said, My usual hour to be up is four. – I’m sorry.

Elderly Kerryman. Michael Hussey, him in the daybreak was driving seaweed in a cart. You thought yous three had hid from me. In the rath. But I was after seeing a strange light • ash at sea the night before. I’m sorry.

Young Kerry boy. Martin Collins, with the pony and trap. At the rath. I seen ye tear a paper up in your hands behind ye, and went back later to see what it was. It was a code, I took it to the polis. I’m sorry what I done.

Middle-aged Kerryman (professional class accent). Doctor Shanahan, the doctor you spoke to in the Barracks at Tralee. I went to get what help I could. But all were under strict orders to do nothing that might abort the Insurrection. I am sorry.25

Or, as it was once put to me directly, ‘They say the local people betrayed him.’

Local stories of Casement’s landing had of course been known in the area around Banna Strand, Fenit, Barrow and Ardfert for years, but they took official form, and went on public record, in April 1966, at the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the Rising. The attitude of the Dublin-centred media from the previous year’s reinterment, expressed in the Irish Times with headlines like ‘Betrayal of Casement through ignorance’, required a response.26 In huge, two-inch boldface letters, the headline of The Kerryman (April 9, 1996) read: ‘ARDFERT IS DEFENDED.’27 The article was largely quotations from a document put together by John Blackwell of Ardfert, a grandson-in-law of the John Allman for whom Mary Gorman had worked. His narrative, like all the other North Kerry material on the subject, not only destigmatizes the Kerry witnesses but restores the details of the testimony to the micro-purposes of all the people involved: a man walking across a field in his work clothes, a boy in a cart, children by a fire. Mary Gorman he describes as ‘a girl who was only two days old when her mother died and got only a few days schooling before making her First Communion’: after the trial she accepted passage to America and never returned to Kerry.28 Martin Collins, says Blackwell, did not turn in the paper (with Casement’s code) as a betrayal but as a favour, saying, ‘You dropped this, Sir.’ After the Civil War, Martin moved to New Zealand and never returned to Kerry. Kearney ‘knew that life in this country would be intolerable’ for him, and he emigrated to England in 1922.29 Casement’s landing had created a mini-diaspora.

Like the relation of ballads to national monuments, according to Luke Gibbons, Blackwell’s stories exist ‘in the margins between the personal and the political, charging a personal event or memory with the impact of a political catastrophe – and vice versa’.30 Blackwell places the witnesses in the most intimate family contexts: he says that when the warrant for Martin came, his mother, who had ten other children, the youngest 5 weeks old, collapsed from the shock and did not recover for half a year. When John McCarthy saw the RIC men coming from a distance, ‘he cleared down the sandhills from them. His wife informed them she did not know where he was. They remained on until nightfall’, so he stayed away from home. They returned two days later ‘at the dead hour of night’, surrounded the house and got him. McCarthy, by the way, refused to accept the witness protection: he said, ‘All I want is to be let out of this wretched place and when I go home I will not be afraid of anyone as I never harmed any person [in] my life.’31

Those sandhills that hid McCarthy from the RIC offer a glimpse of the animate landscape that surrounded the Kerry witnesses, protecting the indigenes but giving trouble to a Times reporter who complained of his ‘weary walk’ after the ‘so-called road’ ended.32 A year later, on the Sunday nearest the anniversary of Casement’s execution, Thomas Ashe (a Kerryman from Dingle) delivered an oration at what the tuppenny pamphlet in which it is reprinted calls ‘Casement’s Fort, Ardfert’. McKenna was already replaced: the territory had been Casementized. Ashe addressed the ‘Men and Women of Kerry’ in an oration that establishes a mutually supportive relationship between hero and landscape. As Ashe represents Casement, he is the deliverer come from the sea:

Since my very childhood on the side of the hill or the shores of Dingle Bay, I heard old native speakers of Corcaguiney tell us of the prophecy by St. Columbcille . . . that stated an O’Donnell would land on the Sands of his native land, and that he would bring liberty to the shores of Ireland . . . this mystical O’Donnell [would] land on the strand with a powerful army and powerful armaments . . . and he did come. The mystical man of Columbcille’s prophecy came; he came unknown, but I tell you he is not unknown today. He did not bring with him that great army . . . but he brought with him a loving heart and an undaunted spirit that will live in Ireland as long as any man will live who believes in the Irish ideals of an Irish republic.33

Ashe’s oration may be the First recorded instance of Kerry revisionism, transforming a military fiasco into a spiritual triumph.

Banna Strand has been the site of many later public rituals. The 1966 Fiftieth anniversary ceremonies in Kerry began at Banna Strand: people were bussed there from Tralee, Ballyheigue, Listowel and all around to acknowledge formally and publicly the official sacralizing of the ground: ‘Air Corps planes will • y low in salute over the sandhills at Banna during the ceremony in which the First sod on the site of a memorial to Roger Casement and Robert Monteith will be turned by Monteith’s daughter, Mrs. Florence Monteith Lynch, who is • ying from New York.’34 The sub-marine captain, another German officer, and three sailors from the Aud were also invited to the ceremony. The inscription on the finished monu-ment reads, ‘At a spot on Banna Strand adjacent to here Roger Casement

– humanitarian and Irish revolutionary leader – Robert Monteith and a third man came ashore from a German submarine on Good Friday morning 21st of April 1916 in furthering the cause of Irish freedom.’

Casement as a tutelary deity exists in especially close relationship with the Kerry witnesses. On Banna Strand he is strong, the liberator, the deliverer, who has come to save the oppressed people. But up from the strand, on the domestic front, they are strong: in the stories told about people’s encounters with Casement in Kerry, they help the mysterious stranger, giving him a welcome that was never reported properly. The stories emphasize the hospitality, not the capture. As Blackwell writes, if only Casement had knocked on a door and explained his situation, ‘the desperate difficulties [he was] placed in would have been solved immediately by any one of those friendly, hardworking, respectable people’.35

One narrative in particular shows the intimacy between Casement and his Kerry friends. As Helen O’Carroll put it directly, ‘My great-grandmother gave Casement a cup of tea.’36 O’Carroll (Director of the Kerry County Museum in Tralee) is John Allman’s great-granddaughter and knows the story from her family. When Martin Collins drove by in that pony and trap, he was bringing the messages from Ardfert to Mrs Allman, and at the same time John A. was walking through the field opposite inspecting his cattle. The two members of the Royal Irish Constabulary were in the process of arresting Casement and noticed that he was too weak to walk, and Allman said, ‘When I go back I will change my clothes and drive you over, as I would be going to Ardfert anyway to do the stations.’37 At that moment Martin Collins drove by, and the RIC commandeered his vehicle (‘a light two-wheeled carriage with springs’), but decided to let Collins return to Mrs Allman First. Thus Casement and Ahern were in the trap; Allman and Collins walked home behind it; and Reilly walked back to Ardfert. Here is Blackwell’s account of the hospitable act that ensued:

Ahern took the messages in and told Mrs. Allman what had happened. She said he [Casement] must be starved with the hunger, that if he liked she would get his breakfast for him. When Ahern asked him he agreed. He helped him off the car and into the kitchen. . . . Mrs. Allman related that he appeared to be a man who did not want any conversation, or was so distressed he was unable to say anything, with the result she carried on with her own work. While he was eating there were only two small children for the most of the time in the kitchen with him, and knowing as he must the incriminating nature of the paper he had in his pocket, why he did not throw the thing into the open fireplace is a mystery.38

Those children were Kitty and Nora, Helen’s grandmother and great-aunt; O’Carroll adds their memory, that ‘they saw this man sitting in a chair coughing and shivering, drinking his tea and eating his breakfast’.39

Casement, it seems, met with hospitality everywhere: John Kearney, the Head Constable at the Tralee barracks, ‘ensured that Casement was treated with the greatest humanity and dignity during his detention’.40 Having recognized Casement even without his famous beard, Kearney ‘realised the important status and international reputation of the prisoner’. Casement was not locked in a cell; instead, he spent the night ‘in the barracks’ kitchen’, sitting much of the rest of the time ‘in the private quarters occupied by John Kearney and his family’: in other words, they took him into their home. ‘We became close friends’, Casement later told his lawyers of the pleasant night spent in gaol in Tralee.41 Were it not for the fact that Casement was ‘detained’, it could almost be said that the Kearneys gave Casement céad míle faílte. Kearney’s children

. . . recollect Roger Casement admitting to their father that he was very hungry. When asked by Head Constable Kearney what he would like to eat, Casement replied ‘I would love a steak.’ This request con• icted with normal Good Friday practice in a Catholic home but the steak was procured and cooked by Mrs. Kearney. It was relished by Casement. He wanted to give the children some token of his appreciation for the hospitality given to him by the Kearney family but John Kearney would not permit it.42

This story makes compatible types of reverence that might ordinarily seem incompatible. Already semi-sacral, Casement with his hunger trumps the sacral dietary customs of Good Friday. Feeding a martyr on his way to execu-tion must surely be an excusable exception to Catholic practice. Casement’s ‘appreciation for the hospitality’ is important to record, but so is Constable Kearney’s sense of professional responsibility. Three value systems – nationalist, Catholic, professional – are invoked, observed and respected in this narrative, which seems constructed, however unconsciously, precisely for that purpose. Mrs Kearney’s acquiescence to Casement’s carnivorous needs shows her intuitive sense of the holiness hovering about Casement. And because Constable Kearney’s nationalism has already been suggested, his adherence to RIC duty on the small matter of the ‘token’ may be mentioned without any anti-nationalist implications.

Casement did, however, leave such a token, and the Kerry Magazine article from which these anecdotes are taken emphasizes the way in which Kearney returned it. Casement left his watch behind, a gesture of reciprocity made in spite of his host’s refusal. The ‘official channels’ by which the watch ought to have been returned to Casement would have been through the colonial state apparatus: it ought to have gone to ‘the County Inspector at Tralee and to the British Authorities via the Inspector General at Dublin Castle’. But closet patriot that he was, Kearney sent the watch ‘to Case-ment’s Defence Counsel’ George Gavan Duffy, as if a host were returning a friend’s property to the person with nearest access to him.43 Both gestures in this exchange were deliberate and oblique: Casement did not give the watch directly, but he left it behind. Kearney did not retain the watch, but he returned it as if to his guest, not as if to his prisoner. The watch’s route affirms a taboo but not precisely illegal friendship, its small gestures of nationalist solidarity made within the confines of the colonial state. The next morning Mrs Larkin, wife of Constable Larkin, gave Casement tea and eggs, for which Casement reimbursed her.44 All of these gestures – the cup of tea, the Good Friday steak, the gift of the watch, the Saturday breakfast

– were invisible to the rest of the world, indeed to the rest of Ireland, but they were remembered in North Kerry, and they were recorded.

Years later, the residents of North Kerry were still thinking about rescuing Casement. Growing up in Spa, near Banna Strand, in the 1940s, the young Margaret MacCurtain used to walk up and down the beach wondering, ‘what if Kerry had risen to the occasion and hidden Casement and helped him to be reunited with the forces in Dublin? How would things then have been different?’ She thought of the whole episode in suppositional mode, also asking herself, ‘if I had been Mary Gorman, what would I have done? could I have made a superior moral decision?’45 In his Kerryman article Blackwell, in similar suppositional mode, relives the fi asco of Austin Stack’s rescue attempt, noting that the car ‘passed through Ardfert at the same time as Ahern and Reilly were looking at the boat in Banna’, but before they had found Casement: ‘As a matter of fact, had the car gone back the short journey to the fort and kept travelling he would [have been] at least 40 miles away from it at the time Reilly saw him there.’46 Although the people of North Kerry were unable to rescue Casement, their stories show how they fed him and pampered him, treating him as a welcome guest. Eighty years later, they were able to rescue Casement relics, situating them in places of safety and honour.

The boat and the dish

Nor is it surprising that religious art and literature both detailed the process of reassemblage of parts into whole and, underlining the nature of part as part, asserted it to be the whole.

(Caroline Bynum, Fragmentation and Redemption: Essays on Gender and the Human Body in Medieval Religion)

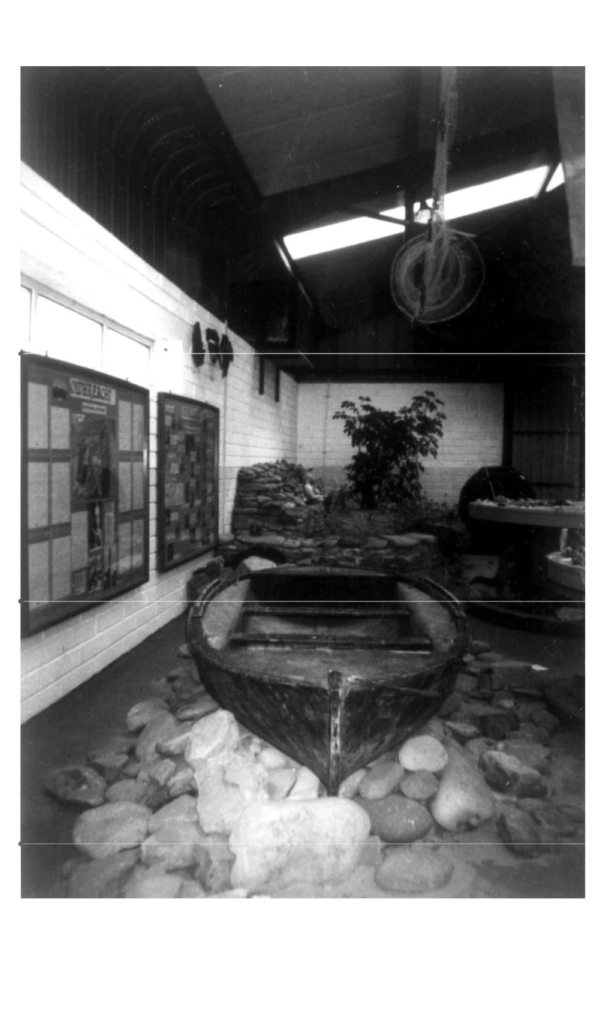

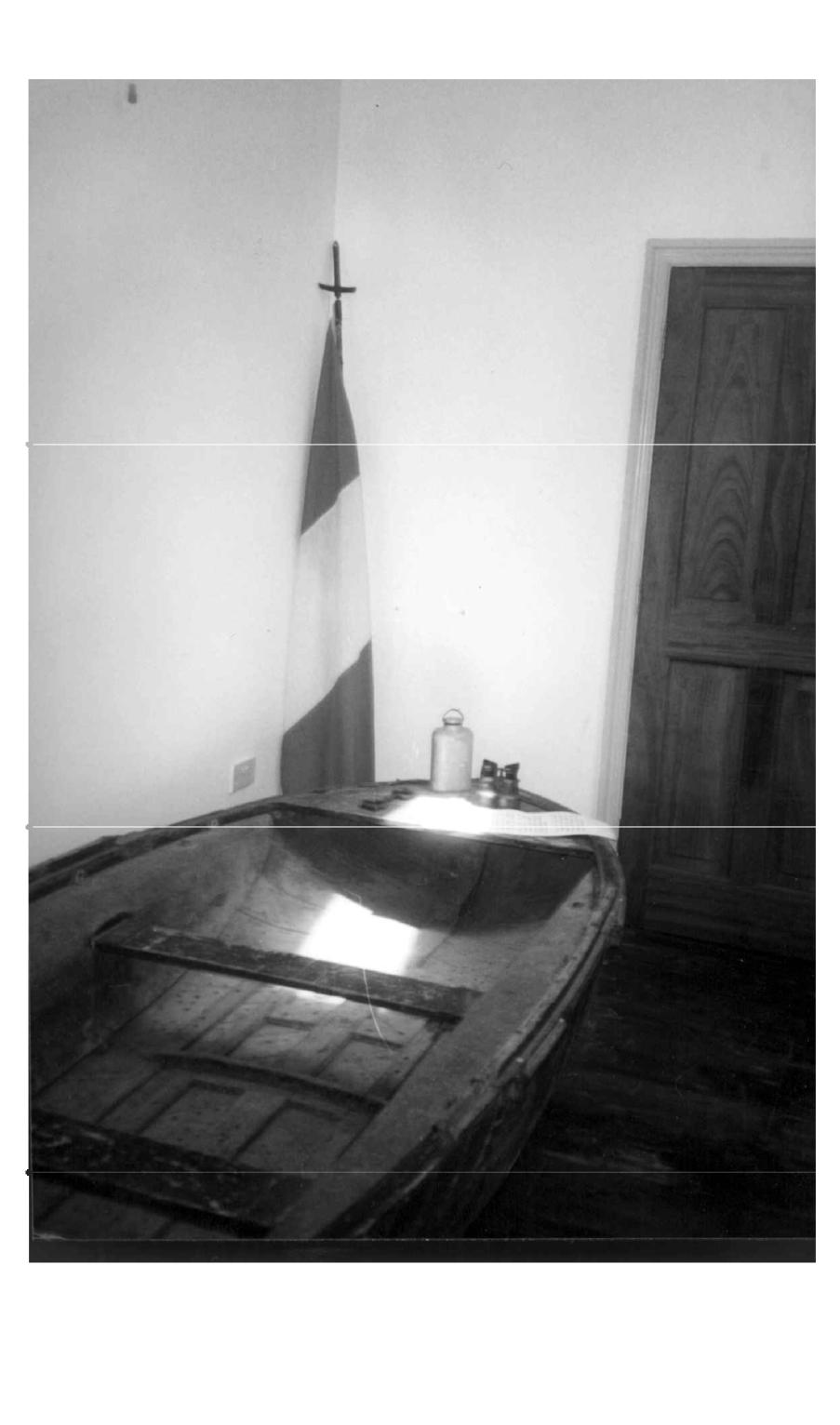

Resting on a pile of rocks under the bizarre looming shadow of the skeleton of the second largest whale ever to have come ashore anywhere, the small grey wooden rowboat looked a little out of place, as most objects would under so many bones. The alleged ‘Casement boat’ certainly did not look holy in the Ballyheigue Maritime Centre, where it was housed between 1996 and 2001. Now in its own small room in the North Kerry Museum at the Rattoo Heritage Centre, where it was translated in the late winter of 2001, the boat has acquired an atmosphere of historical seriousness – a tricolour and period (First World War) binoculars decorate the space – though inevitably it still occupies a secular realm. The large room just outside the boat’s little space, filled with stuffed birds, coats-of-arms, a pulpit, antlers, glass jugs, coach wheels and seashells looks comfortably material. To the south, in Tralee, the Casement dish, framed behind glass

Plate 1 Casement dish in Scoil Mhic Easmainn, Tralee, Kerry. © Breen Ó Conchubhair.

Plate 2 Casement boat in Ballyheigue Maritime Centre, Kerry (1996–2001).

Plate 3 Whale skeleton in Ballyheigue Maritime Centre, Kerry (boat back left).

in the staffroom of Scoil Mhic Easmainn, exists in safe and respectful separation from its surroundings.

These two relics of Roger Casement’s final days derive their meanings not only from the material circumstances in which they are kept but from the narratives of his brief time in North Kerry, and they must be understood in that framework. For years in Cork (the boat) and Dublin (the dish), these relics-in-waiting needed only the right combination of circumstances to get them to Kerry. During their long periods of dormancy, the relics’ status was ambiguous. Patrick Geary’s analysis of medieval saints’ relics shows that their values, also, experienced ‘considerable • uctuations in both the short and the long term’. At the local level, the • uctuation seems directly related First to the impetus of the clerics responsible for promoting the cult – their efforts at elevations or translations (formal, liturgical processions in which remains of saints were officially recognized and transported from one place to another), the erection of new shrines, the celebration of feasts, and . . . second to a rhythm of popular enthusiasm in which miracles seem to have led to more miracles, only to die out again in the course of the year. New efforts on the part of the clergy, or the celebration of the next feast, could begin them anew.47

Plate 4 Casement boat in North Kerry Museum, Rattoo Heritage Centre, Kerry.

A mixture of intense emotion, Celtic tiger prosperity and North Kerry networking ultimately achieved the elevations of the two Casement relics. But even at the low end of that ‘• uctuation’, at times when the objects seem to have been inert or ignored or by default culturally constructed as junk, they were in a sense gravitating towards North Kerry.

The Casement relics have peculiar, though parallel, biographies: from the moment Casement touched them, both were instantly ‘singularized’, never again functional (no one ever put the boat on the water or ate off the dish again) or sold for functional purposes.48 But the planet is full of a lot of clutter, much of it belonging to Irish patriots: in a world that keeps track of Daniel O’Connell’s razor (in the Christian Brothers’ Allen Library), de Valera’s buttons (in the possession of Joseph McGarrity, transferred to Dennis Clarke, who gave them to Kilmainham Gaol), Casement’s pocket handkerchief (in the McGarrity Collection at Falvey Library, Villanova University), Casement’s consular calling card (in the Linen Hall Library, Belfast), and many other bits and pieces, some stuff must occasionally disappear from public access and not be missed. Their biographies show the tendency of objects to sink to the status of clutter, unless otherwise elevated by strong cultural forces.

The boat’s biography is marked by a continually contested status. From the start it was caught up in political con• ict: the imperial war between Germany and England, the colonial con• ict between Ireland and England, and the ideological con• icts of the long-running Roger Casement diary controversy, which made everything to do with his memory potentially embarrassing. If institutions or groups ‘expand the visible reach’ of their own power through asserting the right to define objects, the con• icting cultural definitions of the boat reveal how far that power could reach.49 First, of course, the boat was a vehicle, a purely functional item that could fit inside a submarine. Captain Weisbach refused to give the three disem-barking Irishmen a motor for it, fearing the noise would excite interest, so it was as a rowboat (or dinghy, as it is sometimes called) that it came to Banna Strand.50 Almost from the start of the boat’s Irish history, there was a tendency for the powerful to attempt to minimize interest in it, to keep it inconspicuous. Already it looked like a boat that might create problems. Of this notorious landing Robert Monteith, one of the three men, has written, ‘So there we were, three men in a boat – the smallest invading party known to history.’51

Left alone on Banna Strand, the boat became salvage: around four in the morning a local man, John McCarthy, saw the boat and wanted to turn it in for cash. It was traditionally the right of those who found salvage to claim it – ‘finders keepers’ – but all such finds had to be reported to the RIC. As soon as it was light, a crowd of people stood gazing at all the stuff, several of them taking small items as souvenirs. Before the boat could

be redeemed as salvage it became evidence to be used against Casement. It was photographed in Tralee, once with the arresting Constable and Sergeant standing behind it, and once with the County Inspector of the RIC.52 Not the boat itself, but a photograph of it, was used in London at Casement’s trial for High Treason.53 From Tralee the boat was moved to the naval dockyards at Haulbowline, County Cork.

The boat remained in Haulbowline for eighty years, and in that time its status remained deliberately obscure. Was it old evidence? Great War artefact? dormant relic? Surely after Casement was hanged, it was no longer needed as evidence: why was it kept? Possibly because no one gave an order for it to be destroyed. It is hard to determine how it was culturally con-structed until it emerges into notice again. In October 1950, one Captain Daniel Spicer, formerly of Kerry, a naval officer of the Southern Command stationed in Haulbowline, asked, ‘Is that Casement’s boat?’ and – as Teddy Healy of Ballyheigue tells the story – the officer who answered said, ‘I don’t know, but there’s something special about it. It can’t be moved.’54 For thirty-four years it had been a boat that had ‘something special about it’ and ‘couldn’t be moved’, but whose identity appeared not to be known. Spicer’s interest had been triggered by Monteith’s April 1950 visit to Banna Strand, a ceremonial occasion on which the ‘people of Kerry presented him with an illuminated address as a token of their esteem’.55

Captain Spicer’s correspondence about the boat with a number of people, including Monteith, and Monteith’s correspondence about the boat with the Department of Defence in Dublin, now form part of the boat’s offi cial pedigree. Like the authenticae that confirmed the sacral status of medieval relics or the registration papers that give a dog’s breed, markings and genealogy, the letters in a black binder go with the boat: when the boat was moved from the Ballyheigue Maritime Centre to the North Kerry Museum in late winter 2001, the binder went too. It rests in the museum’s office, where it may be consulted by visitors. The letters are so numerous because the boat’s authenticity was contested for so long: like the submarine captain who didn’t want the boat to be heard, the Irish Minister of Defence didn’t want to hear about it. He must have wanted the problem to go away, but Spicer and Monteith were tenacious.

The cultural construction of the boat as a relic was created through the friendship of Spicer and Monteith. Back on Good Friday 1916, while Casement was attempting to hide in McKenna’s Fort, his two companions went to seek help. (One of them ended up testifying against Casement at the trial.) As the other man, Monteith, tells the story, they sought out the Volunteers in Tralee. Spotting nationalist newspapers in a window, they entered the adjacent newsagent’s shop. The owner was a Mr Spicer, who (after some initial cautious scepticism) called the local Volunteers. Soon Monteith was on the run in southeast Ireland for six months with a £1000 price on his head; the Spicers were the First of many people who helped him.56 This Spicer was the grandson of that family: he had read Monteith’s book Casement’s Last Adventure, and although he had not seen the boat at the time, he had seen photographs of it. He had guessed that the mysterious boat in Haulbowline was the Casement boat, and he got in touch with Monteith, who was then (1950) living in Dublin. In the correspondence related to the attempted authentication of the boat in the early 1950s, about thirty letters between Spicer and Monteith, between Spicer and various naval officials, and between Monteith and the Irish government, the boat itself becomes identified with Monteith’s gratitude for the Spicers’ hospi-tality, both in 1916 and in 1951, when he and his wife stayed with Captain Spicer and his wife.

On the very day he viewed and authenticated the boat (27 October 1950), Monteith told the Cork Examiner how the Spicer family had helped him in 1916, and said, ‘The boat is mine, and if I am allowed to do so I would like to have it presented to the citizens of Tralee, because it was found on the coast of Kerry. The people of Kerry helped me to get away.’57 This Kerry Casement lore writes the story as one of hospitality rather than betrayal: Kerry hospitality saved Monteith’s life. His claim to ownership derives from the German U-boat captain, who singled out Monteith as the one responsible for the boat and gave him lessons in managing it. The boat becomes an item of exchange, his gift to Kerry for harbouring him – just as Casement wanted Chief Constable Kearney to have his watch. The renewed friendship between the two families was inseparable from a kind of reliving of the events of 1916. Mrs Spicer wrote a poem called ‘Casement’s Calvary’, which Monteith praised in one of his letters.58

The Irish government’s resistance to accepting the boat as the genuine article generated a correspondence that forms a classic example of the contest between centre and periphery. The government did not have a fully articulated point of view: the Department of Defence simply objected to every claim advanced by Monteith. When on 31 October 1950 Monteith wrote with his authentication, the Department wrote back that the real boat had been sent to London in 1916 and was in the Imperial War Museum. Monteith wrote to the Museum and got a letter affirming that it wasn’t there, and sent a copy on to Dublin. Finally an official in the Department of Defence, having clearly constructed the boat as a nuisance, wrote to Monteith: ‘I have now had most exhaustive enquiries made into the history of the boat mentioned, and as a result, I am satisfied that it is not the boat used in the Banna landing in 1916.’59 Why these insistent denials? ‘It was because of the homosexuality’, said Teddy Healy.60 To the government, the boat was a dubious minor relic associated with a dubious patriot; to Monteith and Spicer, it was a testimony to hospitality. As Monteith wrote to Mrs S. in 1953,

So the little boat will rot at Haulbowline and the little Gods at Leinster House can sit on their thrones and rub their hands for joy. But there is some good in all evil things. Were it not for the boat it is possible that my wife and I would never have met either you or Captain Spicer.61

Deprived of official status as relic, the boat retained an unofficial sacred status based on the narrative of reciprocal kindnesses between the two families.

It was ultimately Spicer who restored a public dimension of meaning to the boat’s biography, when the fate of ‘the Casement boat’ became intertwined with the fate of a whale carcass. In 1994, a forty-five-ton female finwhale was washed up on the North Kerry coast in Ballyheigue, the second largest whale ever to have been washed up anywhere. Teddy Healy, an enterprising citizen of Ballyheigue whose store faces Ballyheigue Bay, established the Ballyheigue Maritime Centre in order to display the whale skeleton. The ageing Captain Spicer, now in his nineties, got in touch with Mr Healy and said, ‘There’s a bit of a boat in the naval yard you might be interested in.’ They got permission from the Department of Defence, which said, of course the boat officially belonged to the National Museum, but the Ballyheigue Maritime Centre could have it on permanent loan. As for authentication, the Department refused to say that it was the Casement boat, but they didn’t say it wasn’t. In 1996 the boat was installed in the Centre and ‘launched’ by the junior Minister of Defence.62 The object had been reclassified. It was now a provisional relic (maybe it was Casement’s, maybe it wasn’t); it was also salvage – like the whale, an interesting item that had been washed up on the North Kerry coast; a marvel, a tourist attraction, something amazing that people might want to see. When, in 2001, every-one who wanted to see the whale and the boat had seen them, and the Centre was no longer economically viable, both were given new homes: the whale was sent to the Galway aquarium, and the boat, culturally recon-structed as historical artefact, to the North Kerry Museum, whose collection constitutes a kind of attic of regional material culture.

Although the dish also was appropriated by North Kerry in a narrative that emphasized hospitality and emotional reciprocity, its biography forms a contrast to that of the boat, because its authenticity has never been contested. Interest has alternated with indifference in its history, but there has never been a struggle over its status. Like the boat, it begins in functionality. The Seven Stars pub, in Carey Street, London, across from the back entrance to the Royal Courts of Justice, used the plate to serve food. During the time when a prisoner was in court, it was not considered to be the prison’s responsibility to feed him, so he had to obtain food some other way. Casement’s devoted First cousins Gertrude and Elizabeth

Bannister attended the arguments for the appeal of his death sentence at the Court of Criminal Appeal, and it was they who brought him his meals from the Seven Stars on 17 and 18 July 1916. Any First-class or second-class relic of a criminal becomes an instant ‘collectible’, and after the execution the dish became an item of criminal memorabilia, like the objects in Jaggers’ office in Great Expectations: ‘an old rusty pistol, a sword in a scabbard, two dreadful casts on a shelf, of faces swollen and twitchy about the nose.’63 In the twenty-First century as in the mid-nineteenth century and in 1916, a huge market in criminal memorabilia exists, the inverse of the market in saints’ relics. No doubt with an eye to its marketing potential, someone in the Seven Stars pub mounted the dish on the wall with a sign that read, ‘This is the plate from which The Traitor Roger Casement ate his meals on 17 and 18 July 1916.’64

Of course one country’s traitor is another country’s saint, and when Kerryman John Boland, working in London, observed the dish, his cultural construction was different. According to the Irish-language writer Proinsias Mac Aonghusa, Boland told him about the pub with the Casement plate around 1964 or 1965, when Mac Aonghusa was studying film in London. They were eating a pub dinner one night when the subject of the plate came up. Mac Aonghusa said, ‘Do you think it’s still there?’ and Boland said, ‘Let’s go have a look.’ It was early evening, and they went to Carey Street, to the Seven Stars. They sat at the counter and ordered a drink from the licensee, and asked about the plate: ‘Years ago,’ Boland said, ‘there used to be a plate on the wall here. . . . ’ The licensee said, ‘We’re only here since last Monday. The plate’s downstairs in the basement. Do you want to see it?’ Criminal memorabilia had descended to junk. The man got the plate and said to Mac Aonghusa, ‘A pound says it’s yours.’ Mac Aonghusa paid the pound and Boland gave Mac Aonghusa ten shillings, so they became co-owners of the plate.65 Once procured by Irishmen, the plate was reconstructed culturally, its criminality transformed to holiness. The ritual of splitting the cost suggests that ownership of it was an honour, part of a collective identity, not a personal treasure hoard. The act of possession constituted a revision of the object’s identity.

The following day, in an act of restoration, Mac Aonghusa brought the dish to Ireland, intending to give it to a Casement Museum in Tralee. However, the museum never came into being, and the plate remained under a bed in Mac Aonghusa’s house in Blackrock for about thirty-three years. This period of dormancy parallels the time the boat had been identified by Monteith but was ignored by the government; but Spicer didn’t forget the boat, and Mac Aonghusa didn’t forget the dish. It was a relic-in-waiting. In 1998, Pádraig Mac Fhearghusa, a member of Conradh na Gaeilge in Kerry, brought up the subject of the plate, which Mac Aonghusa had told him about long ago. In October 1998 the Oireachtas was being held in Tralee, and Mac Fhearghusa suggested that the plate be presented to Scoil Mhic Easmainn, the Irish-language primary school (in Tralee) named after Roger Casement and founded in 1978 by Mac Fhearghusa and Séan Seosamh Ó Conchubhair.

With this presentation, the plate became a fully realized relic, its status confirmed by display, ceremony and reverence. A special frame, protected by glass, was designed for the dish. The engraved plaque under the plate reads, ‘Casement’s Dish. Presented to Scoil Mhic Easmainn by Proinsias Mac Aonghusa and John Boland. Unveiled by Proinsias Mac Aonghusa on the 25th October 1998 during the Oireachtas.’ Mac Aonghusa says of that day, ‘There was quite a ceremony. They made quite an afternoon of it.’66 The installation ceremony took place in the room where the plate now hangs, the staffroom which is off the main entry hall. On that day, the room was crowded with teachers and students. Mac Aonghusa unveiled the plate and made a speech (in Irish) telling the story of it; then Ó Conchubhair made a speech (also in Irish) about Casement’s ‘loyalty to the Irish language and to Ireland generally’. Then the children in the school bands played some music, and there was a reception with wine and sandwiches.67

In an interview on the subject, Mr Ó Conchubhair said, ‘It was a nice occasion, after all the years to give the platter a permanent home. It had been wandering around all those years.’68 The plate was stabilized at the same time that its sacral nature was confirmed. By synecdoche it had come to stand for Casement, whom the people of Kerry would have taken into their houses if, as a man in Tralee said to me last year, ‘he had only knocked on any door’. At least they could ‘give’ the plate ‘a home’. The engraved plaque adjacent to the plate defines its provenance in a narrative that authenticates it and assimilates it to local social, political and linguistic culture. It says in Irish,

This is the dish from which the patriot and international fighter for human rights, Ruairi Mac Easmainn, ate his meals on the 17th and 18th July 1916, during his appeal before the English Criminal Appeals Court. His loyal First-cousins Gertrude and Elizabeth Bannister brought the meals to the court from the Seven Stars tavern. Roger Casement was hanged in Pentonville Prison on the 3rd August 1916 for his loyalty to Ireland. He was re-interred in Glasnevin Cemetery, Dublin, after a state funeral attended by President Eamon de Valera and other dignitaries on the 1st March 1965. This dish was in the possession of John Boland and Proinsias Mac Aonghusa from the 60s and they presented it to Scoil Mhic Easmainn on Sunday 25 October 1998 during the Oireachtas that was held in the town.69 reimagines the object as part of the surrounding culture, emphasizes reciprocity and hospitality. The ‘loyal’ First cousins love Roger Casement and nurture him, and Casement is ‘loyal’ to Ireland. In the Irish, the same word is used: the cousins are dílis, and Casement’s great loyalty to Ireland is ard–dhílseachta. And North Kerry, which – according to its own stories – fed Casement tea and steak and eggs during his thirty-one hours there, now pays tribute to those feeders Gertrude and Elizabeth Bannister and to Casement by sacralizing the dish that held his food. Unlike the boat, which visitors may sit in and climb on, the dish remains elevated behind glass, a Holy Grail kept safe and apart. Physically more fragile, it is also a more liminal object, less secular, associated more intimately with Casement’s body and with his death.

Guaire knelt before St. Mochua and asked his forgiveness. ‘Thou needest not fear, brother; but eat ye your meal here.’ And when Guaire and his people had taken their meal they bade farewell to Mochua and returned to Durlus. It is a proof of the truth of this story that the Road of the Dishes is the name given to the five miles’ path that lies between Durlus and the well at which Mochua then was. (Geoffrey Keating, Forus Feasa ar Éirinn (A Basis of Knowledge about Ireland), trans. David Comyn and P.S. Dinneen)

The ‘borders between history and story are thin’ in the cultural history of Ireland, Joep Leerssen has written, and ‘literary stories’ are cluttered with ‘factual asides, footnotes, pieces of background information’.70 The narratives of the boat and of the dish exist on one of those thin borders: some might say that their stories are entirely background information. But they also exemplify the way history as well as religion may exist in a different way or be given a different meaning at a distance from the capital. Just as holy wells, in Lawrence Taylor’s analysis, constitute an alternative to the more formalized and centralized powers of the ecclesiastical establishment, so these relics in North Kerry constitute an alternative to the State’s version of patriotism and commemoration of its heroes.71 In the boat, Monteith seemed to want to capture the power of Casement, a power the Department of Defence wanted to neutralize by denying the boat’s authenticity. The Oisín Kelly statue of Casement that now dominates the harbour at Ballyheigue was also rejected by Dublin but rescued for North Kerry by Teddy Healy.72 Like the statue, the boat and the dish are no doubt subject to varying cultural constructions. Even if they are not criminal memorabilia, they may be considered Casement kitsch by the metropolitan tourist. But the distinct yet parallel struggles to get them to North Kerry suggest their importance in a populist devotion more intense and more personal than official patriotism. Casement’s arrival in Kerry in 1916 made the whole area liminal. The stories about the ‘betrayal’ of Casement and the instability of the man in national memory have led to the acquisition of objects in North Kerry that assert both the sacral nature of the space he walked through and the reverence of the local people, now hospitable to his relics – so long as the relics stay put.

For many kinds of help in and about Kerry, the author would like to thank Isabel Bennet, Maura Cronin, Tom Finn, Teddy Healy, Liam Irwin, Margaret MacCurtain, Deirdre McMahon, Helen O’Carroll, Breen Ó Conchubhair and Philip Tindall.

1 The phrase and the idea of a ‘charismatic landscape’ are borrowed from Lawrence J. Taylor, Occasions of Faith: An Anthropology of Irish Catholics

(Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1995), pp. 46, 48.

- John Blackwell, ‘Ardfert is defended’, The Kerryman, Saturday, 9 April 1966,

- Florence Monteith Lynch, The Mystery Man of Banna Strand (New York: Vantage Press, 1959), p. 137.

- To view the pistol in the RUC virtual museum, visit <http://www.psni.police. uk/museum/text/captions/sec4pl1.htm>. There was great interest in acquiring Casement’s guns. Major G. H. Pomeroy Colley and Major Price both requested Casement’s revolver. Basil Thomson of Scotland Yard wrote to Colley, ‘If it is in any way possible, I will see that you get one of Casement’s revolvers. One of them is bespoken for the Museum, and another has been promised to Major Price, but I do not think anything has been decided yet about the third one’ (PRO MEPO 2/10670).

- L. Reid, The Lives of Roger Casement (New Haven, CT, and London: Yale University Press, 1976), p. 357. For the practices of the United Irishmen in creating and distributing relics, I am indebted to Mary Helen Thuente’s unpublished paper ‘United Irish artifacts and icons: the memory of the dead’, June 2001.

-

- Conversation with Brother Thomas Connolly, Allen Library, Christian Brothers, North Richmond Street, Dublin, January 2002.

</ul

-

-

- Typed letter from Captain Daniel D. Spicer to Executive Officer, Southern Command, 8th June 1951, p. 3; in black binder of authenticating materials about ‘Casement Boat’, North Kerry Museum, Rattoo Heritage Centre, Kerry.

-

- 25 July 1916. NLI 13077. As cited in B. L. Reid, The Lives of Roger Casement,

- ‘Licensing application of John Collins, Ardfert’, Kerry Sentinel, 4 November 1916. Reference courtesy of Deirdre McMahon.

-

- Conversation with Anne Casement, Dublin, May 2000.

- Igor Kopytoff, ‘The cultural biography of things: commoditization as process’, in Arjun Appadurai (ed.) The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), pp. 67, 68.

-

- Richard Murphy, ‘Casement’s funeral’, The Price of Stone & Earlier Poems (Winston-Salem, NC: Wake Forest University Press, 1985), pp. 49–50.

- Caroline Walker Bynum, Fragmentation and Redemption: Essays on Gender and the Human Body in Medieval Religion (New York: Zone Books, 1991), p. 295. The story of Casement’s bones – not relics because they are buried in Glasnevin – makes an interesting parallel to the stories of the boat and the dish. For commentary on it, see Lucy McDiarmid, ‘The posthumous life of Roger Casement’, in Anthony Bradley and Maryann Valiulis (eds.) Gender and Sexuality in Modern Ireland (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, published in cooperation with the American Conference for Irish Studies, 1997), pp. 127–58, and Deirdre McMahon, ‘Roger Casement: an account from the archives of his reinterment in Ireland’, Journal of the Irish Society for Archives, n.s., 3 (1) (spring 1996), pp. 3–12.

-

- Conversation with Beth Kiberd (granddaughter of James Moriarty), Dublin, June 1996.

-

- ‘Trial of Sir Roger Casement’, Irish Times, 17 May 1916, p. 5.

- The complicated story of precisely who was arrested, where, when and how, when Stack and Collins tried to rescue Casement, is told in many places with somewhat differing details. See Blackwell, ‘Ardfert is defended’, p. 8; ‘Trial of Sir Roger Casement’, Irish Times, 17 May 1916, p. 5; and Robert Monteith, Casement’s Last Adventure (Dublin: Michael F. Moynihan, 1932; rpt. 1953), 164.

-

- This information can be found in many places. Blackwell’s ‘Ardfert is defended’ is the most detailed; see also Reid’s The Lives of Roger Casement.

-

- Conversation with Tom Finn (son of Lizzie Boyle), Tralee, May 2000.

- See Reid, The Lives of Roger Casement, pp. 355–7; and Donal O’Sullivan, ‘The fate of John B. Kearney, District Inspector of the R.I.C. and Superintendent of the Civic Guard’, The Kerry Magazine, 9 (1998), pp. 19–23.

-

- Deirdre McMahon, ‘Maurice Moynihan (1902–1999) Irish Civil Servant: an appreciation’, Studies, 89 (353) (spring 2000), p. 71.

-

- Donal O’Sullivan, ‘The fate of John B. Kearney . . . ’, pp. 22–3.

- Conversation with Helen O’Carroll, Tralee, 1999.

- ‘Banna Strand’, Unsigned, Irish Opinion (15 July 1916), p. 5.

- See n. 12.

- David Rudkin, Cries from Casement as his bones are brought to Dublin (London: BBC, 1974), p. 70.

-

- Irish Times (24 February 1965), p. 4.

- ‘Ardfert is defended’, The Kerryman (9 April 1966), pp. 1, 8.

- , p. 8.

- Donal O’Sullivan, ‘The fate of John B. Kearney . . . ’, p. 23.

- Luke Gibbons, Transformations in Irish Culture (Cork: Cork University Press in association with Field Day, 1996), p. 145.

-

- Blackwell, ‘Ardfert is defended’, p. 8. John McCarthy wanted more than his passage home: his solicitor, Henry Walsh of The Square, Tralee, submitted a claim for £103 ‘for loss sustained to his crops whilst absent from home’. The

- 25 July 1916. NLI 13077. As cited in B. L. Reid, The Lives of Roger Casement,

-

items listed ranged from ‘loss on early potato crop’ ( £10) and ‘loss of turnip crop’ (£10) to ‘loss through illness of child’ (£4) and ‘amount paid in labour working the farm in his absence’ (£9). In the same letter, Walsh said that McCarthy ‘claims to be allowed reward for the finding of the boat’ (Public Records Office MEPO 2/10671).

Casement. How He Was Captured. Sleeping in an Old Fort’, The Times (London), 3 May 1916, p. 3.

-

-

- ‘Oration delivered by Commandant Thomas Ashe at Casement’s Fort, Ardfert, Co. Kerry, on Sunday 5 August 1917’ (NLI IR 94109). Quoted by permission of the Keeper of Collections, National Library of Ireland.

-

- ‘Banna Strand Memorial Ceremonies’, The Kerryman (9 April 1966), pp. 1, 8. One of the earliest plays about Casement was Traigh Bhanna, a translation into Irish by Seamus Ó Dubhda from the English of John MacDonagh, presented at the Peacock Theatre, Dublin, as one of three dramas commemorating the Rising (Irish Times, 15 April 1936, p. 8). At least two novels about Casement have centred on Banna Strand: Mount Kestrel by ‘An Philibín’ (Dublin: M. H. Gill and Son, 1945) and The Knight of the Flaming Heart by Michael Carson (New York: Doubleday, 1995). The famous ballad ‘Banna Strand’ was written in 1965.

-

-

-

- Blackwell, ‘Ardfert Is Defended’, p. 1.

- Interview with Helen O’Carroll, Tralee, July 1995.

- John Blackwell, ‘Ardfert is defended’, p. 8.

- Interview with Helen O’Carroll, Tralee, May 2000.

- Donal O’Sullivan, ‘The fate of John B. Kearney’, p. 20.

- L. Reid, The Lives of Roger Casement, p. 356.

- Donal O’Sullivan, ‘The fate of John B. Kearney’, p. 20.

- , pp. 20–1.

- L. Reid, The Lives of Roger Casement, p. 357.

- Conversation with Margaret MacCurtain, Spa, Kerry, July 1995.

- John Blackwell, ‘Ardfert is defended’, p. 8.

- Patrick Geary, ‘Sacred commodities: the circulation of medieval relics’, in Arjun Appadurai (ed.) The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective, p. 179.

-

ul>

- The term is taken from Igor Kopytoff, ‘The cultural biography of things’, passim. Kopytoff uses the term to signify that an object has been ‘decom-moditized’, i.e. it is no longer ‘exchangeable or for sale’ (p. 69).

- , p. 73.

- Robert Monteith, Casement’s Last Adventure, p. 150.

- , p. 151.

- Undated clipping from the Irish Press (probably October 1950) in black binder of boat’s papers, North Kerry Museum, Rattoo Heritage Centre, Kerry.

- Typed letter to Captain Spicer from Garda C. G. Seevers about interview with Mr B. Reilly (who had been one of two RIC men arresting Casement on Good Friday 1916), 10 October 1950; in black binder of boat’s papers, North Kerry Museum, Rattoo Heritage Centre, Kerry.

- Interview with Teddy Healy, Ballyheigue, Kerry, May 2000.

- Florence Monteith Lynch, The Mystery Man of Banna Strand, p. 132.

- For the complete account of Monteith’s adventures between the moment of his separation from Casement and the time of his arrival in New York, see his

Casement’s Last Adventure.

57 ‘Casement’s boat identfied. Capt. Monteith tells the story’, The Cork Examiner, Saturday, 28 October 1950. Unpaged clipping in black binder of boat’s papers, North Kerry Museum, Rattoo Heritage Centre, Kerry.

- Typed letter to Captain Spicer from Robert Monteith, 16 November 1950; in black binder of boat’s papers, North Kerry Museum, Rattoo Heritage Centre, Kerry.

- The letter is dated 28 July 1951; it is reproduced in Florence Monteith Lynch,

The Mystery Man of Banna Strand, p. 135.

- Interview with Teddy Healy, Ballyheigue, Kerry, May 2000.

- Copy of handwritten letter to Mrs Spicer from Robert Monteith, 20 November 1953; in black binder of boat’s papers, North Kerry Museum, Rattoo Heritage Centre, Kerry.

- Information in this paragraph taken from interview with Teddy Healy, Ballyheigue, Kerry, May 2000.

- Charles Dickens, Great Expectations, Chapter 20.

- Interview with Proinsias Mac Aonghusa, Dublin, May 2001.

- Interview with Seán Seosamh Ó Conchubhair, Tralee, June 2001.

69 Irish original by Proinsias Mac Aonghusa; English translation by Breen Ó Conchubhair.

- Joep Leerssen, Remembrance and Imagination: Patterns in the Historical and Literary Representation of Ireland in the Nineteenth Century (Notre Dame, IN: Notre Dame University Press in association with Field Day, 1997), p. 226.

- Lawrence Taylor, Occasions of Faith: An Anthropology of Irish Catholics, pp. 35–76.

- Interview with Teddy Healy, Ballyheigue, Kerry, May 2000.